Download the full survey as low res PDF [1.4 MB] or in print resolution [30 MB]

The female:pressure FACTS survey quantifies the gender distribution of artists performing at electronic music festivals worldwide, and has published reports since 2013.

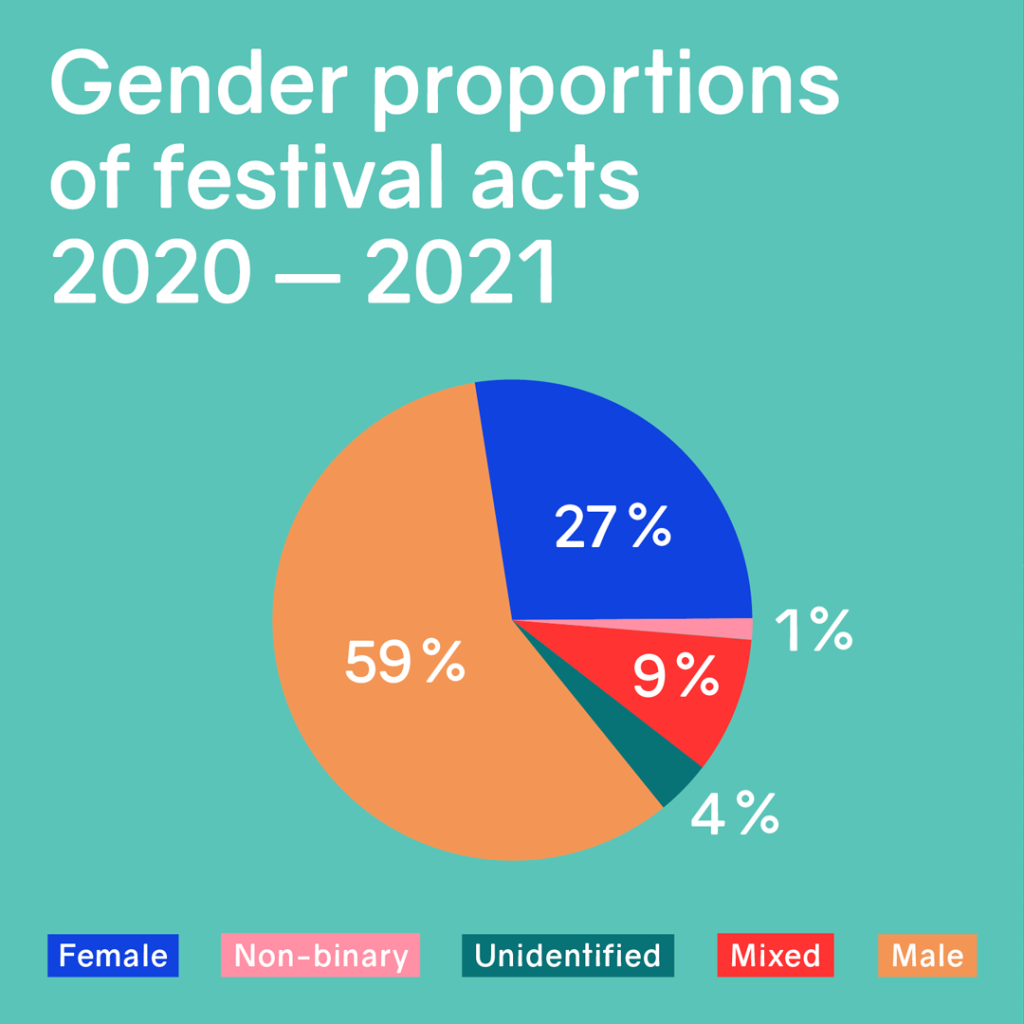

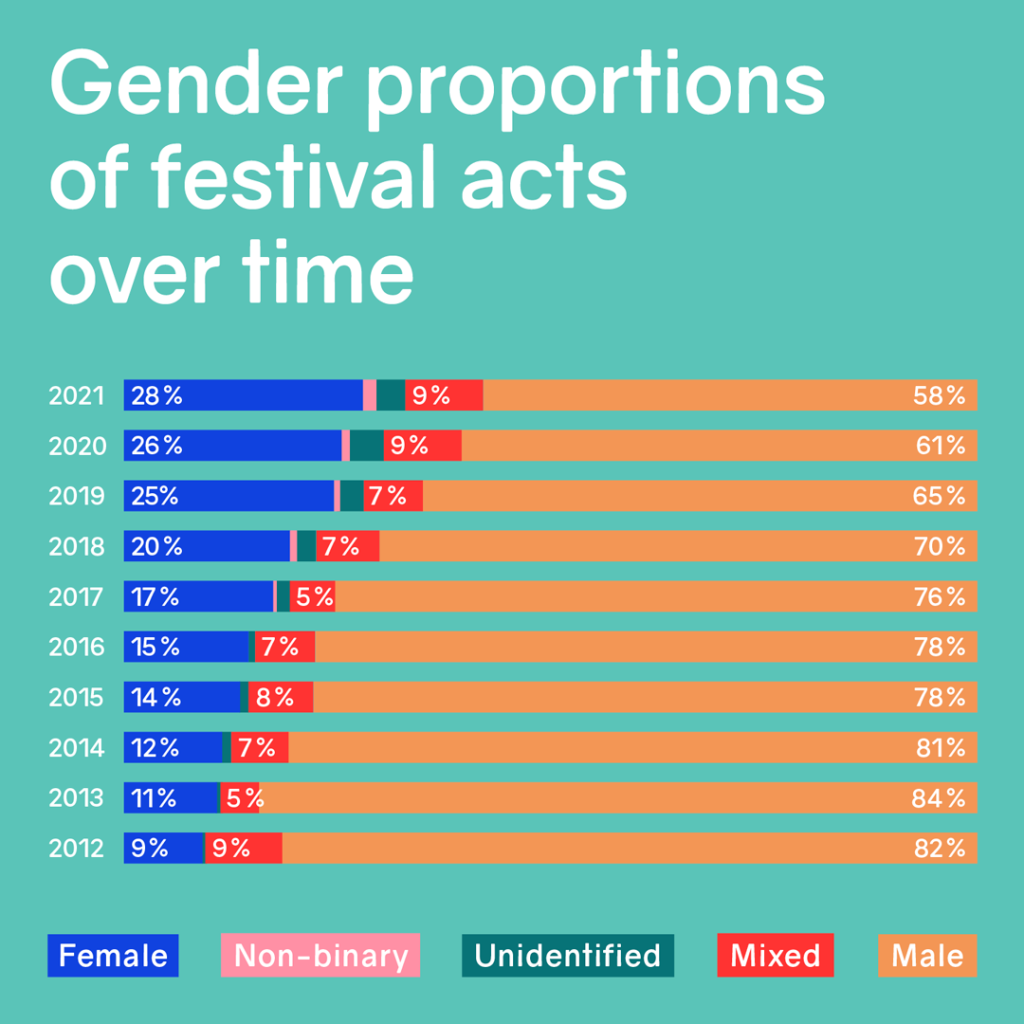

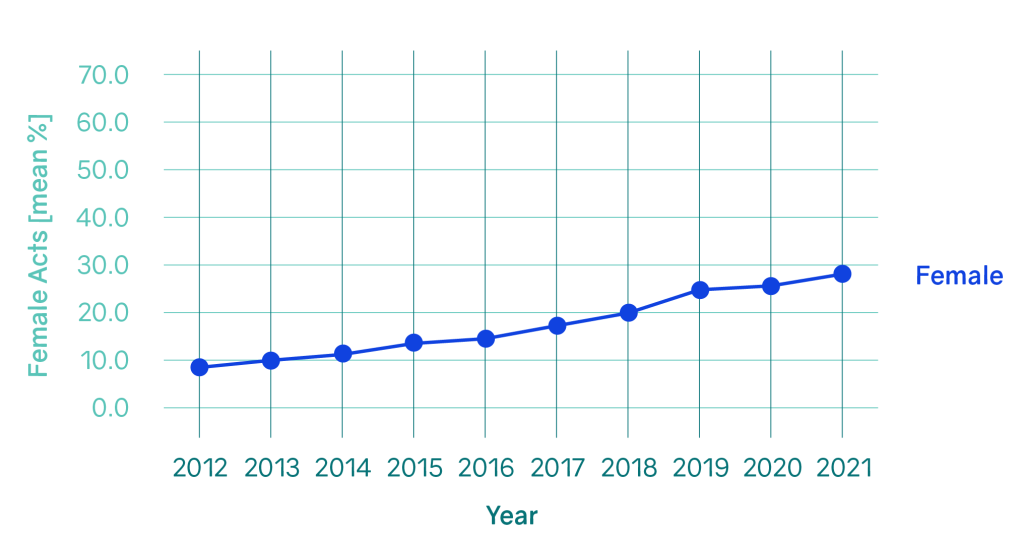

FACTS 2022 reveals a rise in the proportion of female acts from 9.2% in 2012 to 26.9% in 2020–2021. The data on non-binary artists shows an increase from 0.4% to 1.3% from 2017 to 2021.

The FACTS 2022 report also includes a section on further issues of diversity such as racism and ageism, and a Call to Action with specific suggestions for festival organizers, artists, journalists, policy advocacy groups, and festival attendees.

Summary

Background

The female:pressure FACTS survey is a continuous project undertaken by volunteer members of the female:pressure network to quantify the gender distribution of artists performing at electronic music festivals worldwide. FACTS 2022 is the fifth edition of the survey, which was first published in 2013, and updated in 2015, 2017, and 2020.

Methods

Data was provided by the female:pressure Trouble Makers, female:pressure members, and festival organizers. Gender proportions for each festival are assessed for female, male, non-binary [starting 2017], and mixed acts [more than one gender]. The number of acts are counted per slot of stage time. “Acts” include musical and visual artists or bands who appear on stage/on screen, as they are listed in the festival’s program.

Results

We collected data for 159 festival editions [of 109 unique festivals] that took place in 2020 and 2021. Adding this to the previous survey data, female:pressure has collected data for 833 festival editions [264 unique festivals in total] from 2012 to 2021 from 48 countries. The proportion of female acts rose from 9.2% in 2012 to 26.9% in the current reporting period of 2020 to 2021. As of 2021, 1.3% of all acts surveyed are non-binary and 9.1% are mixed in comparison to 59.1% male acts. Larger festivals tend to have lower proportions of female and non-binary acts. Publicly funded festivals and festivals with female artistic directors have higher proportions of female acts.

Conclusion

Conclusion: We see a slow but steady rise in female and non-binary acts in electronic music festivals over the past decade. However, with female and non-binary acts comprising only a little over a quarter of all artists booked, there is still a significant imbalance in gender representation on electronic music festival stages today.

FACTS 2022 – Introduction

FACTS 2022 – Methods

FACTS 2022 – Results

FACTS 2022 – Discussion

FACTS 2022 – Additional Issues of Diversity

FACTS 2022 – Call to Action

FACTS 2022 – Credits and Provisions

FACTS 2022 – Appendices

1. INTRODUCTION

The female:pressure FACTS survey is a continuous project that quantifies the gender distribution of artists performing at electronic music festivals worldwide. The survey is undertaken by volunteer members of the female:pressure network. FACTS 2022 is the fifth edition of the survey, which was first published in 2013 and updated in 2015, 2017, and 2020.

The FACTS survey was initiated in 2012 to address and quantify the lack of equal opportunity and visibility for female artists in the electronic music scene, with the first edition published in March 2013. The results of FACTS 2013 indicated that barely 10% of acts at electronic music festivals worldwide were women, opening up an international discussion about the state of women’s opportunities in electronic music.

In 2015 and 2017, we updated and extended the survey. Although the inequities within the industry had become a popular topic of debate since the 2013 edition, FACTS 2015 demonstrated the continued underrepresentation of women artists at electronic music festivals. FACTS 2017 marked a new, more thorough approach to conducting and presenting the survey as the methods of data collection and analysis were more explicitly defined. The survey was more comprehensive than previous surveys [including more festivals than previously], and the results showed an improving situation regarding the gender balance. Newly introduced in FACTS 2020 were the non-binary gender category, as well as data on: the attendance numbers of a festival, whether or not it received public funding, and the gender[s] of its artistic director[s]. In order to quantify the response of festival organizers to the COVID-19 pandemic, the FACTS 2022 survey collected data on how the festival was presented [onsite, online, or hybrid].

Over the course of 2020 and 2021 our team reached out to all of the festivals included in the survey, inviting festival organizers to participate by submitting their data. [Note: Our list of festivals consists of festivals included in the previous editions of FACTS as well as relevant festivals not previously included that were suggested by a female:pressure member or other member of the public.] We always appreciate having organizers respond to our call, as it reduces the amount of data that we need to collect ourselves. For FACTS 2020, thirty festival organizers responded, more than double the amount of responses we received for FACTS 2017, which we speculated was the result of increasing publicity and research about gender equality in the music industry. Surprisingly, 28 festival organizers submitted gender data for FACTS 2022, a decrease of only two from the previous edition, even though over 130 festival editions in our list were canceled over the 2020–2021 time period.

By observing how little the percentage of female and non-binary artists has increased over the past decade of FACTS surveys, we see the extent to which inequality is a systemic issue. Structural sexism perpetuates inequality by creating barriers and disincentives for artists of marginalized genders, limiting success in the arts to the status quo. While this phenomenon is receiving more media coverage today, we believe that measuring trends through the FACTS survey is necessary to understand developments in the electronic music industry and to hold decision-makers accountable.

In adding the non-binary category to the previous edition of the survey [FACTS 2020], we confronted an important question in our data collection process: How should we address systemic bias in a direct manner without inadvertently reinforcing the reductive language commonly used? We had many discussions regarding the use of the terms “female,” “non-binary,” and “male,” delving into the meanings that societies place upon these terms, and whether it was useful at all to categorize artists this way. Ultimately, we adopted these three terms, despite being an organization that recognizes many more genders beyond these categories, because the industry as a whole generally does not. To address the industry’s inequality, therefore, necessitates the use of the language of the industry.

Our FACTS survey, like the female:pressure network, is the result of grassroots activism, conducted independently from any organization and without external funding. The 2022 edition of the survey was undertaken by nine core volunteers, nicknamed the “Trouble Makers,” with the aid of twelve helpers.

2. METHODS

Aims and Objectives

The aim of the present survey was to assess the gender distribution among artists performing at electronic music festivals around the world.

Specifically, we wanted to:

- assess the gender proportions among artists performing at electronic music festivals taking place in the years 2020 and 2021;

- assess time trends in gender proportions from 2012 to 2021; and

- assess differences in these gender proportions for regions, countries, and other festival characteristics.

Gender proportions are assessed for female, male, non-binary, and mixed acts [non-binary only for data starting in 2017].

Data Collection

Data was collected for all countries worldwide with no restrictions. We used a standardized online form to collect single sets of data for each festival edition.

The survey’s focus is on electronic music festivals. The Trouble Makers assembled the list of festivals from previous FACTS surveys, lists of electronic music festivals found online, and suggestions from the female:pressure network and the general public. Festivals were included if they featured a mainly electronic music program. Once a festival was included, all acts were counted regardless of their musical genre.

For each festival, the following data were collected:

- Name of festival;

- World region;

- Country;

- City;

- Year;

- Number of female acts in the line-up;

- Number of male acts in the line-up;

- Number of non-binary acts in the line-up [starting in 2017];

- Number of mixed [two or more genders in one time slot] acts in the line-up;

- Number of unidentified [gender unknown] acts in the line-up;

- Whether public funding was received [starting in 2017];

- Number of attendees [starting in 2017];

- Gender of artistic directors [starting in 2017]; and

- How the festival was presented: onsite, online, or hybrid [starting in 2020].

The number of acts were counted per slot of stage time. For example: Dasha Rush & Donato Dozzy back-to-back DJ-set: categorized as 1 mixed act. Electric indigo & Thomas Wagensommerer a/v set: categorized as 1 mixed act. Lucrecia Dalt & Gudrun Gut live: categorized as 1 female act.

“Acts” include musical and visual artists or bands who appear on stage, as they are listed in the festival’s program line-up. We did not count installations, film screenings, or discourse programs.

For the purpose of this survey, gender data is distinguished and collected as female [persons using the pronouns she/her], non-binary [persons using the pronouns they/them, or other combinations], and male [persons using the pronouns he/him]. Transgender artists are categorized according to the gender pronouns used in artist bios, social media, etc. We used publicly available biographical data about the artists to determine what pronouns they used, either by visiting their websites and/or social media, or by searching for articles about the artist. Cis-male artists with female aliases/monikers were categorized as male artists if they use the pronouns he/him. In cases where an artist’s pronouns or identity could not be found, the artist was categorized as “unidentified.”

Data was provided by the Trouble Makers, female:pressure members, and festival organizers. Festival organizers were emailed standardized letters over the course of two years explaining the background and the purpose of the survey along with an invitation to enter their festival data into a short online form. To minimize data entry errors, we were able to verify about 34% of the newly collected data [2020 to 2021] with a second or third data count. A margin of tolerance was set at 5% of the mean total number of acts per festival edition. The difference between the first and second count for each gender category should be equal to or less than the tolerance margin, otherwise a third [final] count was done by an experienced group member.

Data Analysis

Data was analyzed descriptively. Female, male, non-binary, mixed, and unidentified gender proportions are presented numerically and graphically: overall, by year, by country, by region, and by other festival characteristics. In addition, trends over time for specific festivals [with data for several time points] are presented. Mean [i.e., average] percentages are calculated by adding the number of acts for the specific gender divided by the total number of acts [times 100] for each festival. Due to rounding, numbers presented throughout this document may not precisely add up to 100%.

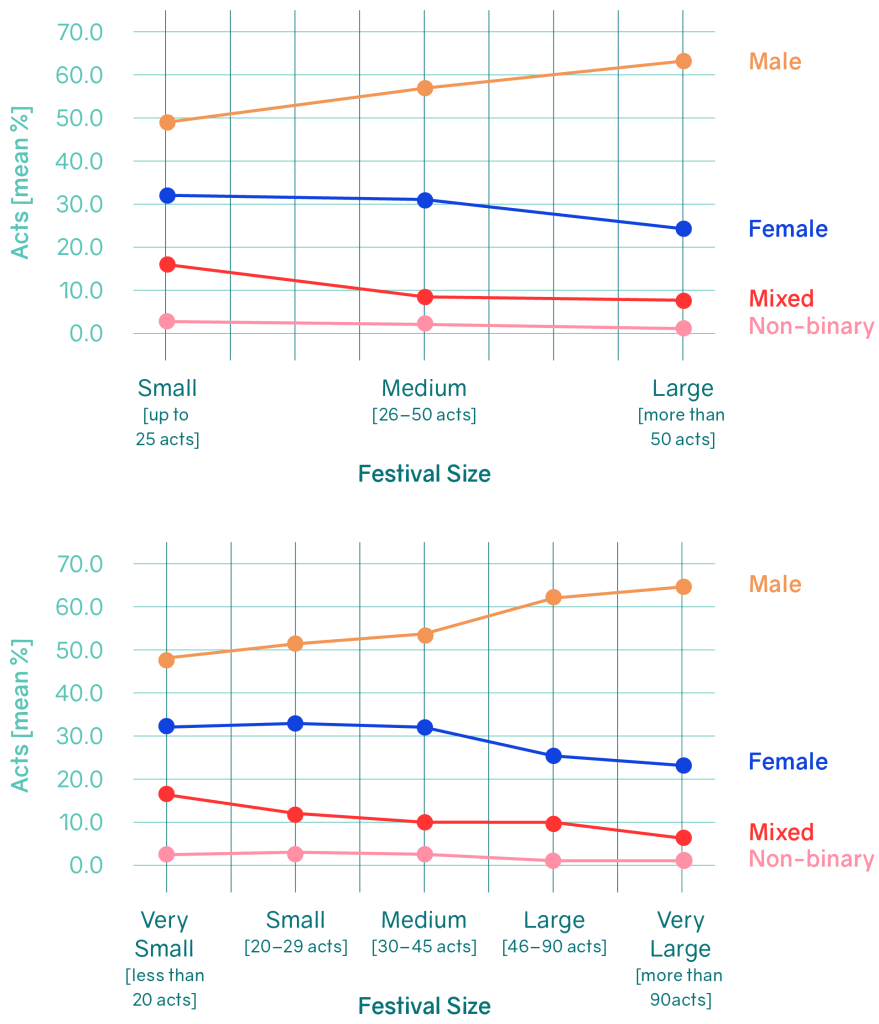

Festivals were also categorized and analyzed by the total number of acts. To see if gender proportions vary with the size of the festival, we categorized festivals into three groups: small [up to 25 acts], medium [26 to 50 acts], and large [more than 50 acts], as well as into five more refined groups: very small [less than 20 acts], small [20 to 29 acts], medium [30 to 45 acts], large [46 to 90 acts], and very large [more than 90 acts]

For data from 2017 onward, festivals were also categorized according to whether public funding was received, the audience size [attendance numbers], and the gender of the festival’s artistic directors. For data from 2020 onward, festivals were categorized according to how they were presented [onsite, online, or hybrid].

3. RESULTS

Number of Festivals and Festival Type

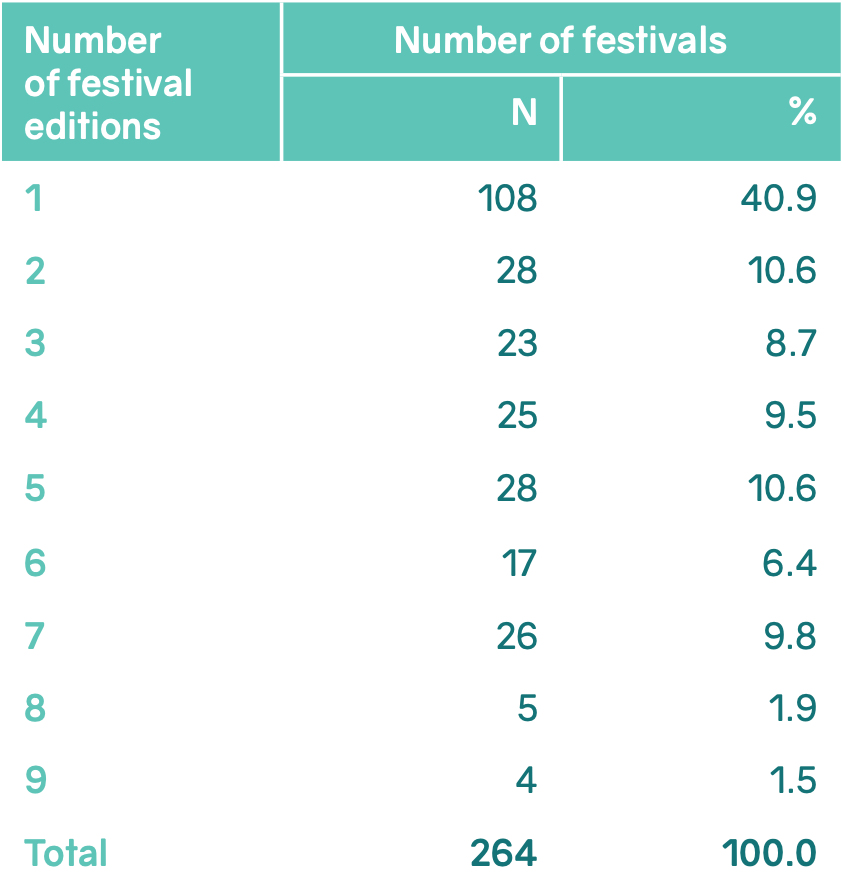

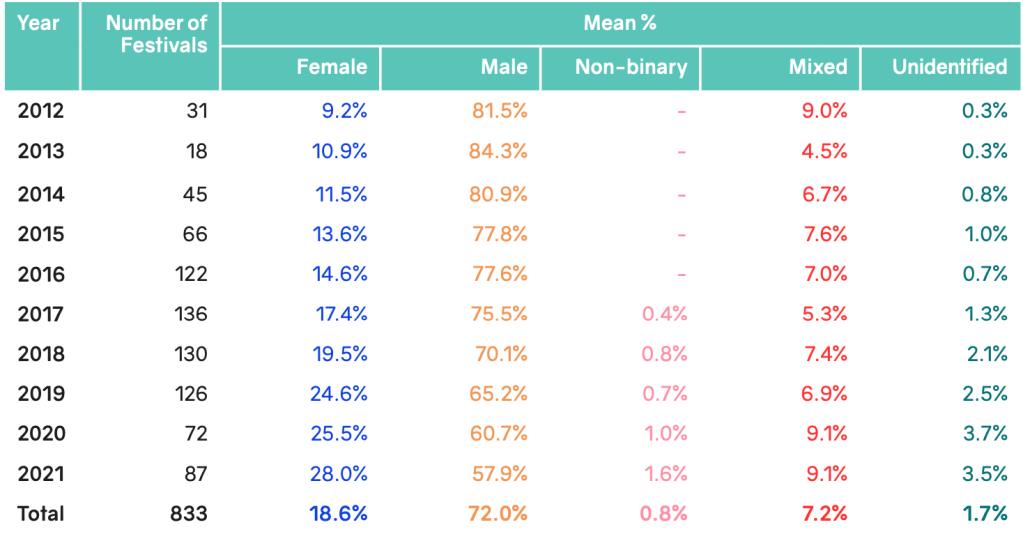

In this edition of the survey, we collected data for 159 festival editions [of 109 different festivals] from 2020 to 2021. This includes 72 festival editions in 2020 and 87 in 2021. Adding this to the previous data, female:pressure has collected data for 833 festival editions [264 festivals] from 2012 to 2021 [Table 1].

Table 1. Number of festivals by year

For 2017 to 2019, festivals from 37 countries were included with 287 [73%] festival editions For 2020 to 2021, festivals from 35 countries were included with 118 [74.2%] festival editions from Europe and 19 [11.9%] from North America. For 2012 to 2021, festivals from 48 countries were included. Data for 108 festivals were collected only once, while data for 28 festivals were collected at two time points [i.e two yearly editions]. For 128 festivals, data are available for 3 or more years between 2012 and 2021 [Table 2].

Table 2. Number of festivals with amount of editions counted [n,%]

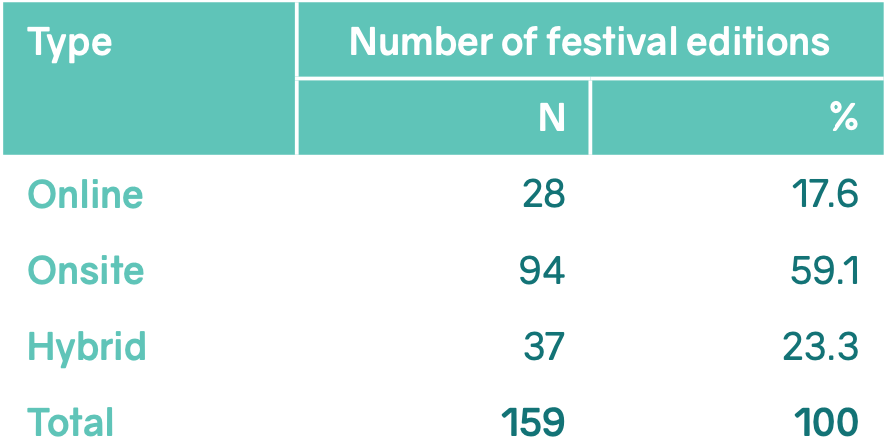

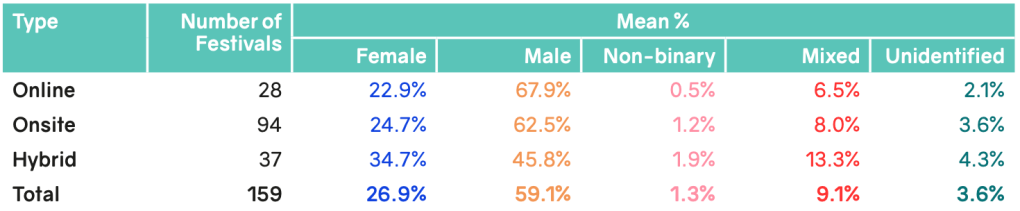

For the years 2020 and 2021, we categorized festival editions as either online [no in-person events], onsite [all events take place in-person], or hybrid [a mixture of online and in-person events]. The majority of festival editions [59.1%] took place onsite despite the pandemic [Table 3].

Table 3. Type of festival [n,%] [2020 to 2021]

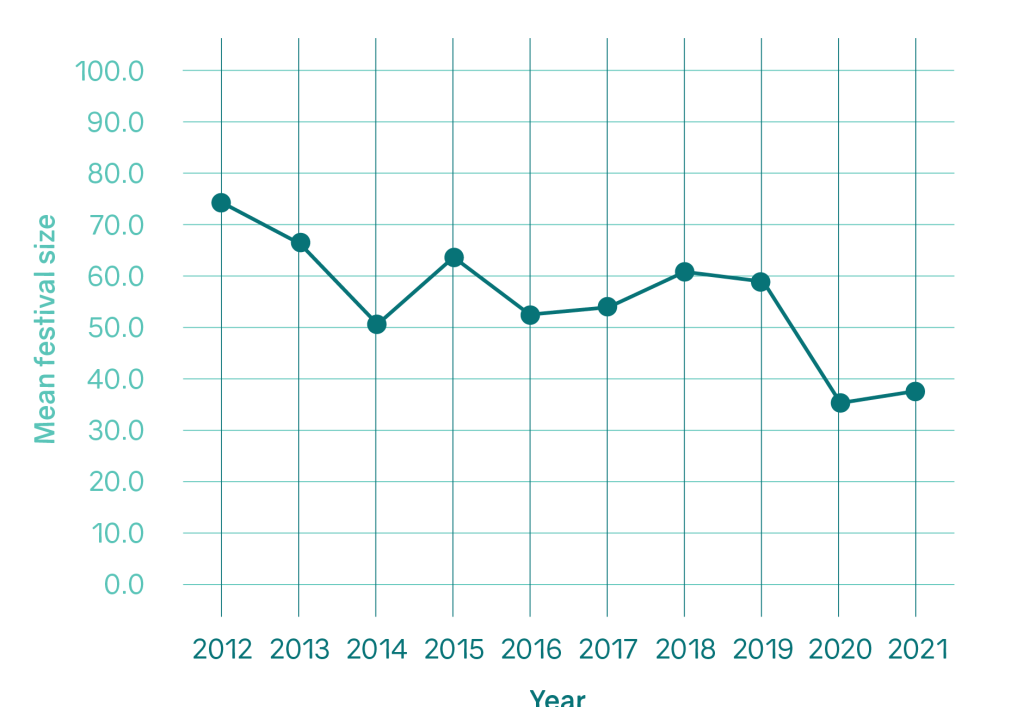

The mean [i.e., average] festival size was 54.1 acts with a minimum of 2 and a maximum of 726 acts per festival; in total, 45,104 acts are included [2012 to 2021]. For the current period of 2020 to 2021, festivals have a mean of 37.8 acts [minimum of 2, maximum of 316] and a total of 6,015 acts. During the pandemic years, this total number of acts is significantly less than in the period from 2017 to 2019, for which we analyzed 22,651 acts. Accordingly, the mean festival size [in number of acts] decreased in 2020 and 2021 [Figure 1].

Gender Proportions of Festival Acts

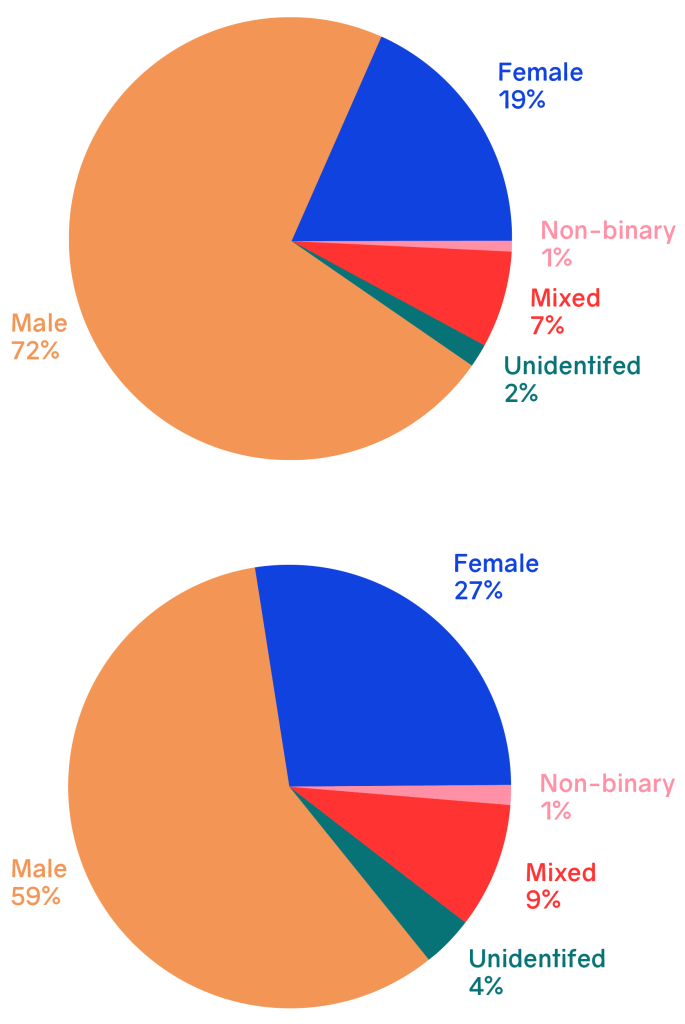

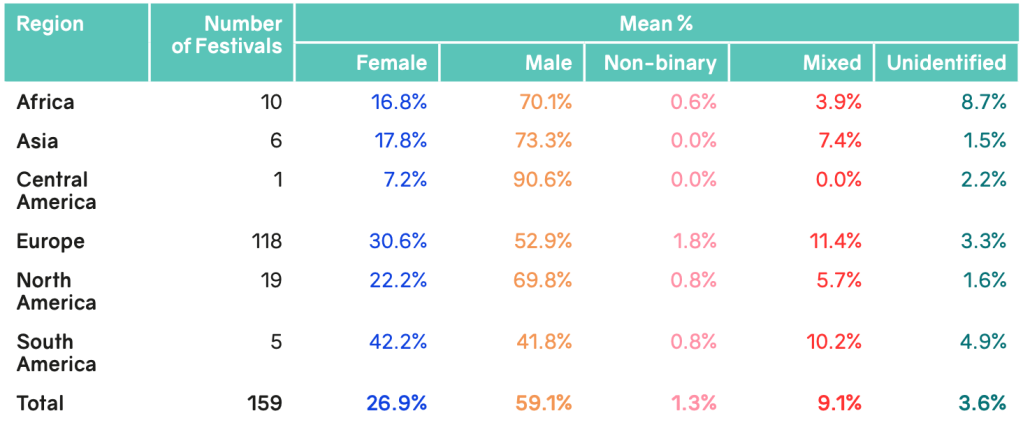

For the period from 2012 to 2021 overall, 18.6% of acts are female, 72.0% are male, 7.2% are mixed acts, 0.8% are non-binary acts [starting from 2017], and 1.7% are unidentified [i.e., acts where the gender could not be identified] [Figure 2, above]. For the newly collected data for festivals from 2020 to 2021, there are 26.9% female acts, 1.3% non-binary acts, 59.1% male acts‚ 9.1% mixed, and 3.6% unidentified acts [Figure 2, below].

Gender Proportions over Time

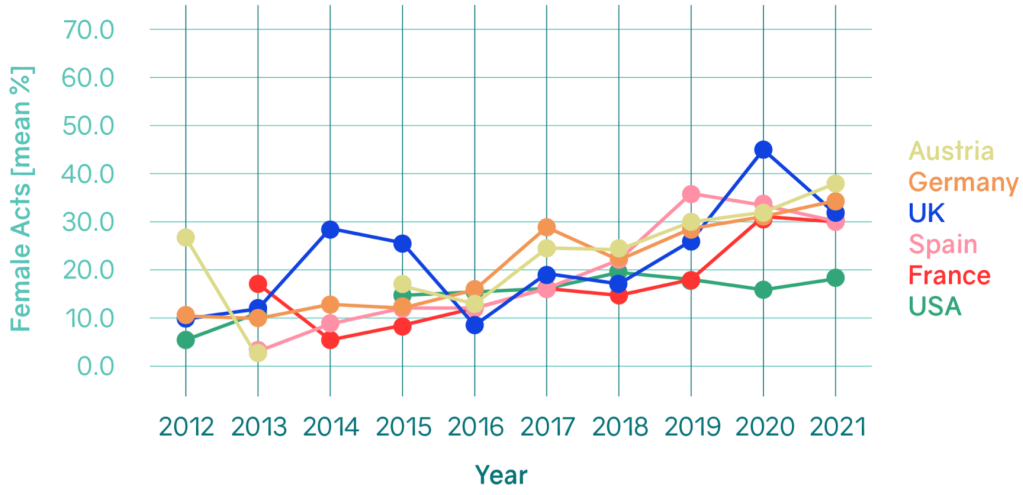

From 2012 to 2021, there is an increase in the number of female artists and a decrease in the number of male artists [Figures 3 and 4].

Table 4 shows the proportions of female, male, non-binary, mixed, and unidentified acts for each year from 2012 to 2021.

Table 4. Female, male, non-binary, mixed, and unidentified acts in % over time

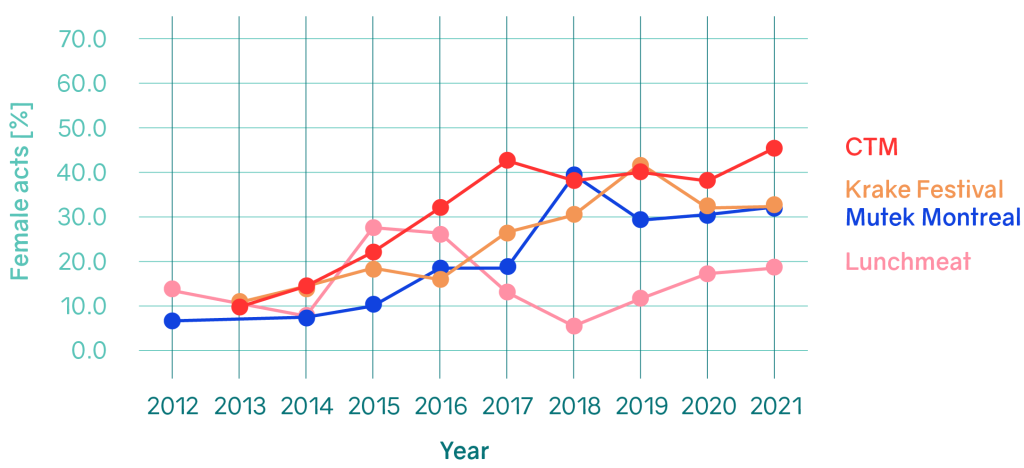

For festivals with data for 9 years, we assessed changes over time per festival. Figure 5 shows the percentage of female acts for each festival. There appears to be an overall trend of increased female acts for several festivals. Results for all festivals by year are shown in Appendix 1.

Gender Proportions for Different Regions

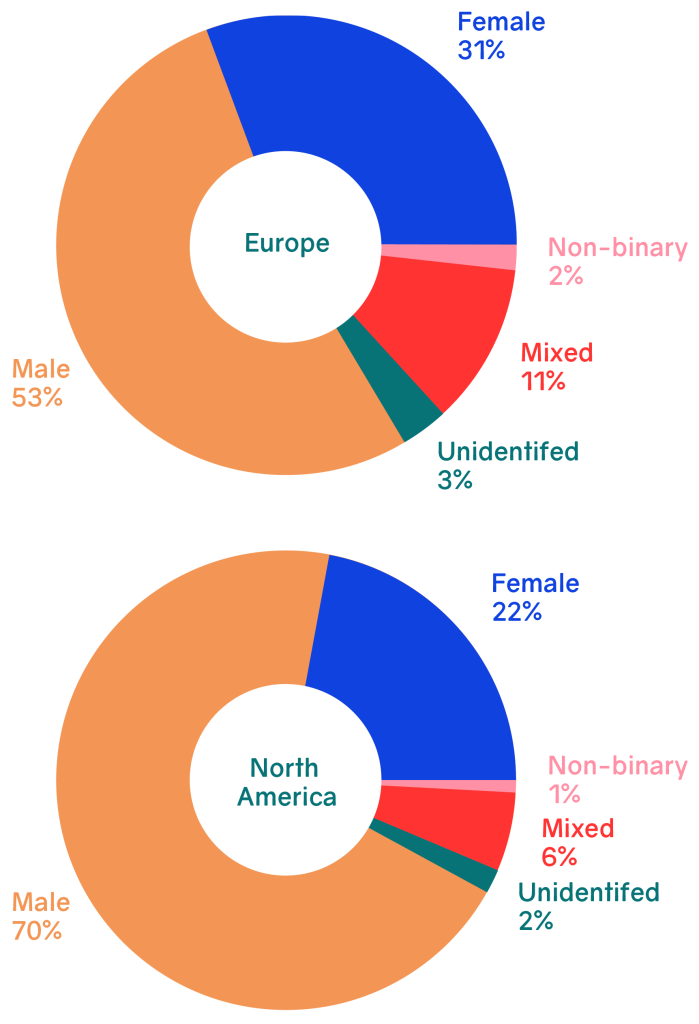

Comparing festivals across regions from 2020 to 2021, there were 30.6% female acts at all European festivals and 22.2% female acts at North American festivals [Figure 6].

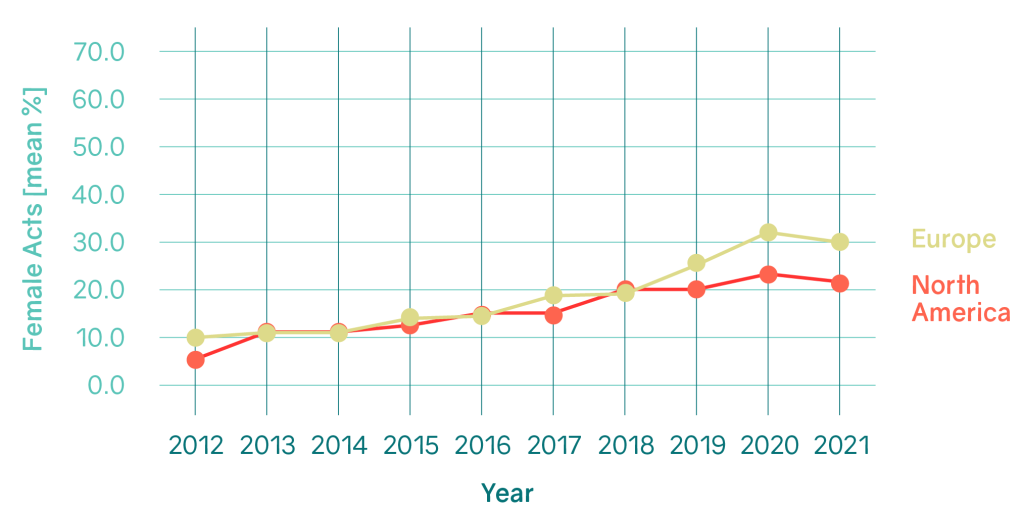

In addition, we analyzed the proportions of female acts for European and North American festivals over time [Figure 7].

Results for further regions are shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Gender proportions for all regions [2020 to 2021]

Gender Proportions by Country

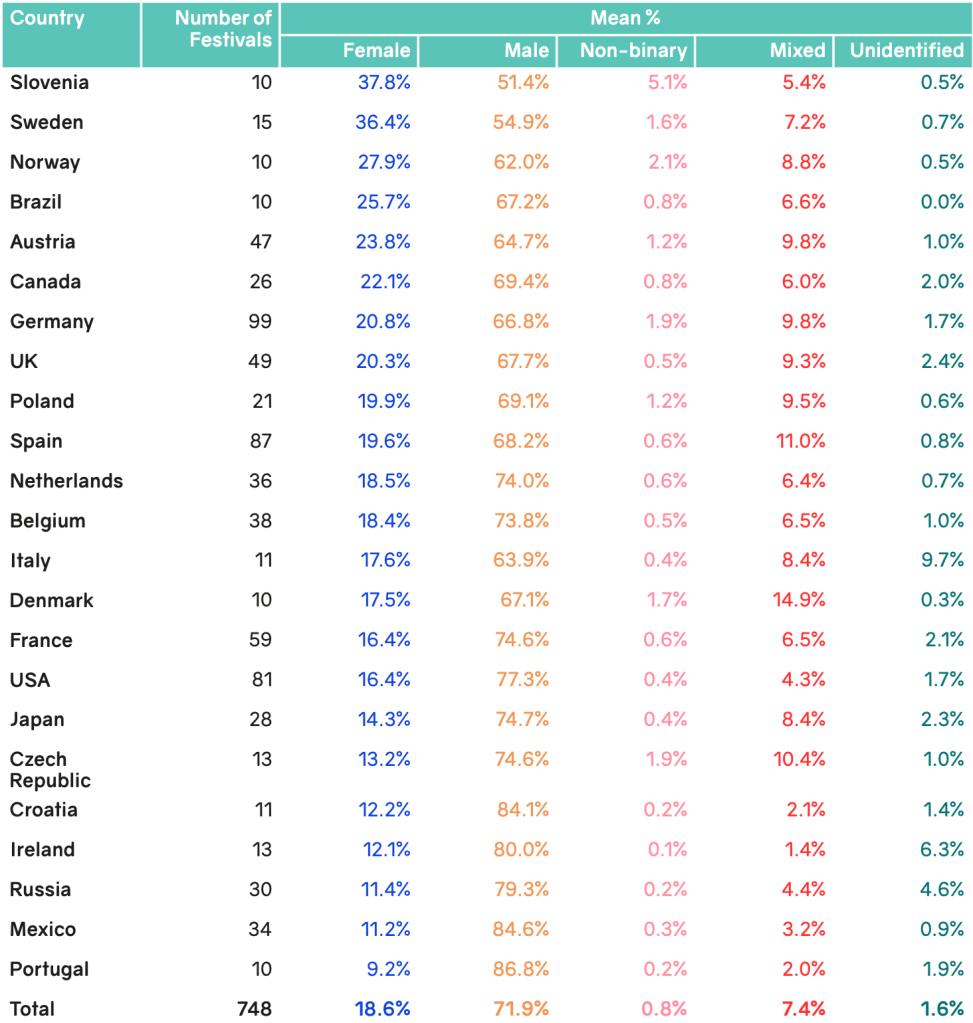

Gender proportions are quite different when comparing across countries. For example, from 2012 to 2021, festivals in Portugal, Mexico, and Russia have the lowest percentages of female acts [less than 12%] while festivals in Slovenia and Sweden have the highest percentage [over 36%]. Table 6 shows the proportions of female, non-binary, male, mixed, and unidentified acts by country for 2012 to 2021 [only for countries with ten or more festivals].

Table 6. Gender proportion of acts by country [2012 to 2021]

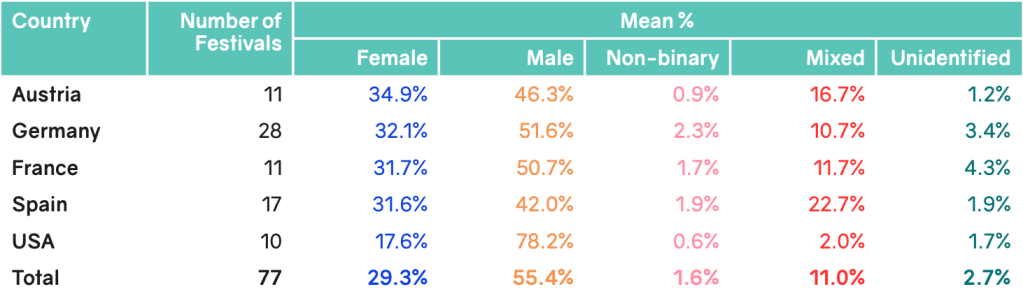

In the current counting period from 2020 to 2021 we did not have as many countries with ten or more festival editions as in previous counting periods. Table 7 shows the proportions of female, non-binary, male, mixed, and unidentified acts by country [again only for countries with ten or more festival editions].

Table 7. Gender proportion of acts by country [2020 to 2021]

We also analyzed the proportions of female acts over time for the six countries with data for the most festival editions: Austria, France, Germany, Spain, UK, USA [Figure 8]. Results for all countries are shown in Appendix 2 and results for all countries and respective festivals are shown in Appendix 3.

Gender Proportions by Size of Line-Up

To assess if gender proportions vary with the size of the festival program, the number of total acts was used to categorize festivals into three groups [Figure 9, above], as well as into five more refined groups [Figure 9, below]. In general, the smaller a festival line-up, the higher the percentage of female acts. Conversely, larger festivals tend to have higher percentages of male acts. Results for all festivals from 2012 to 2021 by size of line-ups are shown in Appendix 4.

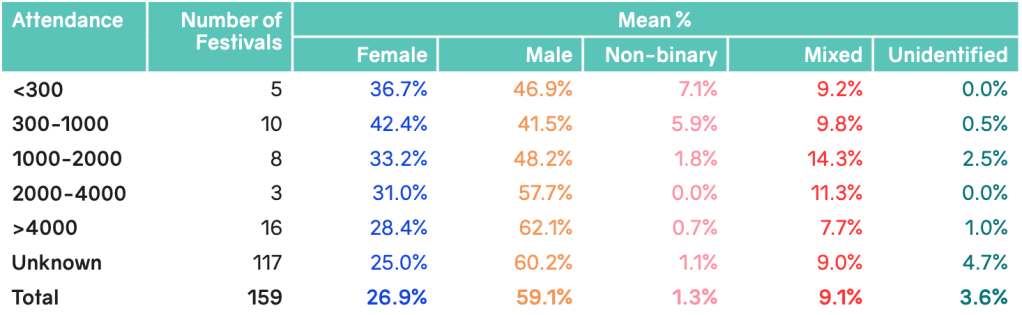

Gender Proportions by Audience Size

In addition to categorizing festivals by the number of acts, we used the approximate number of visitors [attendance] to classify festivals according to size. Table 8 shows gender proportions by the number of visitors for festivals taking place in 2020 and 2021. As we saw in the comparison of festival size by line-up, similarly, festivals with larger audience sizes are also associated with higher proportions of male acts.

Table 8. Gender proportions by audience size [attendance] [2020 to 2021]

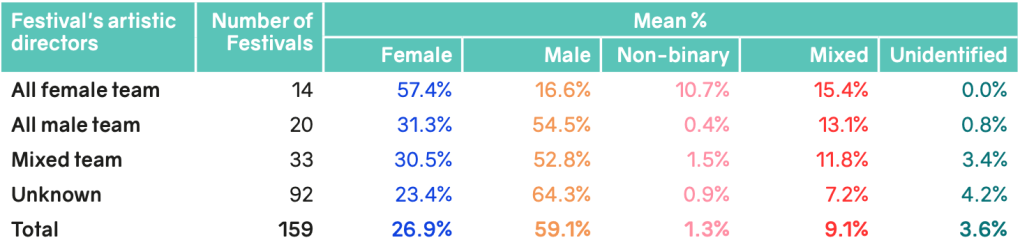

Gender Proportions by Gender of Curators

To assess an association between the gender of a festival’s artistic directors and the gender of the performing acts, Table 9 shows data for 2020 to 2021. The proportion of female and non-binary acts is highest for festivals with an all female team: 57.4% and a striking 10.7%, respectively. The proportion of female acts is similar for festivals with an all male team, or a mixed team [a team whose members are of different genders]: 31.3% and 30.5%, respectively. Notably, for 57.9% of all festival editions that we counted for 2020 and 2021 we could find no information on who curated the line-ups. More transparency from electronic music festival organizers about who is curating their line-ups would be beneficial for these analyses.

Table 9. Gender proportions by the gender of festival’s artistic directors [2020 to 2021]

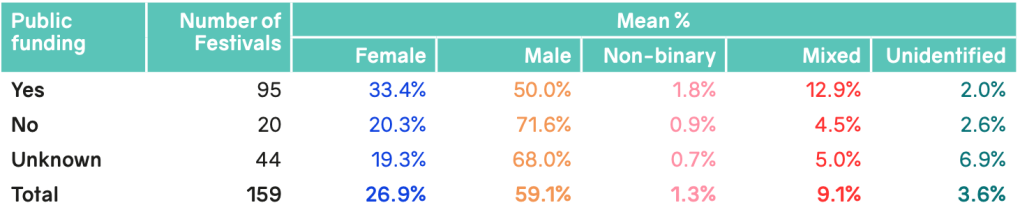

Gender Proportions by Funding

To assess whether gender proportions differ by funding source, we assessed whether festivals were publicly funded. Table 10 shows data for 2020 to 2021. For festivals with public funding the percentage of female acts is 33.4%, and for festivals with no public funding the percentage of female acts is 20.3%. Here again, for 27.7% of festival editions taking place in 2020 and 2021 we could not determine whether public funding was used; more transparency on how festivals are funded would also benefit the analysis.

Table 10. Gender proportions by public funding [2020 to 2021]

Gender Proportions by Presentation Type

The percentage of female acts from 2020 to 2021 was fairly similar for online and onsite events, but higher for hybrid festivals [34.7%]. The proportion of mixed acts almost doubled, comparing online events with festivals in hybrid forms. [Table 11].

Table 11. Gender proportions by type of festival [2020 to 2021]

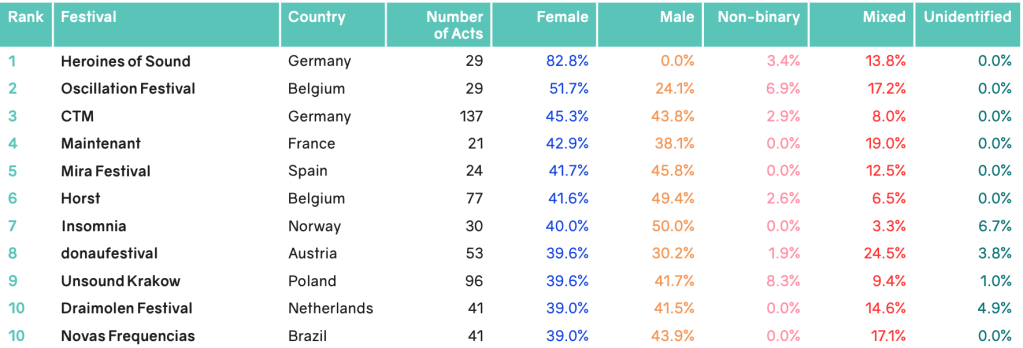

Top 10 Festivals with the Highest Proportions of Female Acts

For the years 2020 and 2021, we assessed the festivals with the highest proportion of female acts and ranked them. This was only done for festivals with 20 or more acts. Results for the ten highest ranking festivals are shown in Tables 12 and 13. Results for all festivals are shown in Appendix 5.

Table 12. Top ten festivals by female proportion in 2020 [for festivals with at least 20 acts]]

Table 13. Top ten festivals by female proportion in 2021 [for festivals with at least 20 acts]

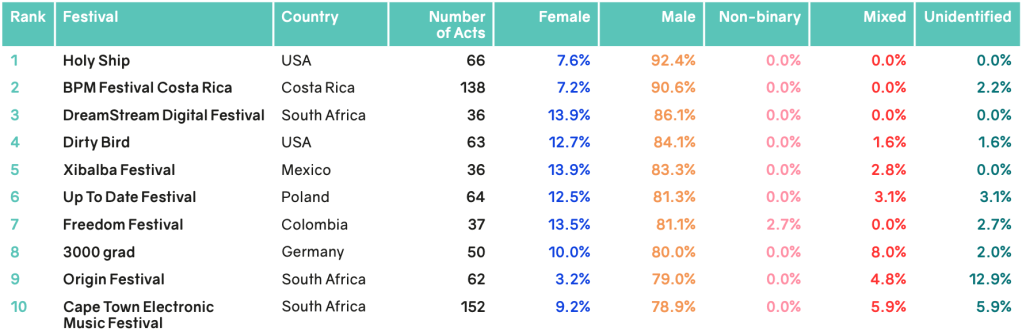

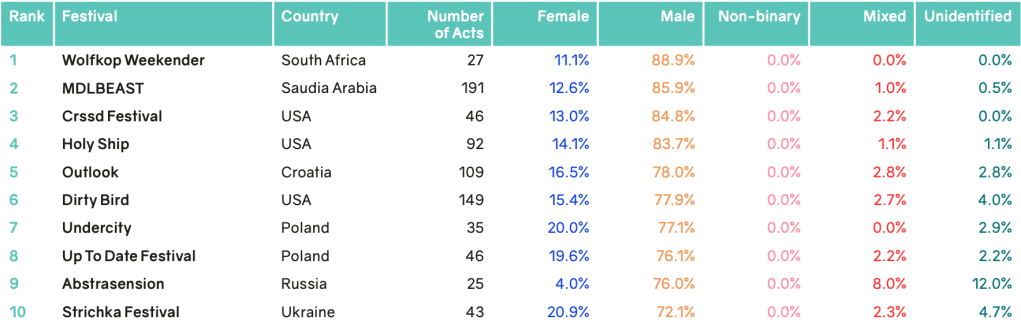

Top 10 Festivals with the Highest Proportions of Male Acts

Similarly, we assessed the festivals with the highest proportion of male acts [for festivals with 20 or more acts only]. Results for the ten highest ranking festivals are shown in Tables 14 and 15. Results for all festivals are shown in Appendix 6.

Table 14. Top ten festivals by male proportion in 2020 [for festivals with at least 20 acts]

Table 15. Top ten festivals by male proportion in 2021 [for festivals with at least 20 acts]

4. DISCUSSION

Summary of the Results and Conclusion

In our present survey assessing festival acts from 2020 to 2021, we found that 26.9% of all acts were female, 59.1% were male, 1.3% were non-binary, and 9.1% were mixed. The proportion of female acts overall rose from 9.2% in 2012 to 26.9% in the 2020 to 2021 counting period.

We see a steady rise in female acts in electronic music festivals over the past ten years. However, only 26.9% of all acts are female in comparison to 59.1% male acts.

Comparison with Other Studies

Black dance music without Black people: a data analysis. February 2022.

This analysis by Non-Governmental Organisation Technomaterialism tracks the representation of Black artists in event lineups across 27 countries in the EU in 2020 and 2021. They collect lineup data from event pages on Resident Advisor, a similar approach to FACTS although the FACTS report is focused specifically on festivals, and includes international data from a wider array of sources. The Technomaterialism report uses the Black Artist Database as a means of identifying Black artists. They also include Black population data for selected countries.

Music Business Worldwide, “Here’s what women are earning (compared to men) in the UK music industry”. October 2021.

Using publicly available gender data about UK businesses with 250 or more employees MBW examined the UK gender pay gap numbers for Universal Music, Sony Music, Warner Music, Apple, Spotify, and Live Nation. The mean average pay gap ranged between 15.3% and 34.3% across the 6 companies; for example, the mean average hourly rate of pay across the whole of Warner Music UK in April 2020 was 30% lower for women vs. men. MBW’s study is similar to FACTS in that they analyze gender; the study also represents an aspirational [though likely impossible] goal for FACTS, which would be to analyze the pay gap among the larger festival lineups.

Equality and Diversity in Concert Halls. July 2021.

This study presents an analysis of works by women composers scheduled in the 2020/2021 season by 100 orchestras from 27 countries. While previous reports in 2018/2019 and 2019/2020 focused solely on gender the current report includes data for Black and Asian composers by gender. The findings: 11.45% of scheduled concerts included compositions by women. Compositions by Black and Asian women made up 1.11%, Black and Asian men made up 2.43%. The criteria for evaluating the gender and race of composers are not described in the report.

Black Radioactive Boi [Twitter handle TokenOfTheMonth]. July 2021.

BRB published an analysis of race and gender for the festivals Lost Lands and EDC. The findings: the Lost Lands lineup was only 5.5% women, all of them white; the EDC lineup was only 8% women. The thread continues with more festivals analyzed. New data is now being posted in the @EDMnumbers account.

https://twitter.com/TokenOfTheMonth/status/1416946734295625733?s=20

https://twitter.com/TokenOfTheMonth/status/1416561206933049348?s=20

Towards gender equality in the cultural and creative sectors. June 2021.

This report analyzes gender gaps and imbalances in the cultural and creative sectors in the EU and connects them with wider structural issues of gender equality such as pay gap, career advancement, and access to the labor market and art market. One of their key findings is a lack of consistent data on gender in these sectors across Europe, making it difficult for policy makers to address them.

Inclusion in the Recording Studio? Gender and Race/Ethnicity of Artists, Songwriters & Producers across 900 Popular Songs. March 2021.

This report assesses gender and race/ethnicity of artists, songwriters, and producers across the 900 most popular songs from 2012 to 2020, based on the Billboard Year-End Hot 100 Chart. In addition, the analysis breaks down artist data by type – solo, duo, or band. The findings: 21.6% of artists in the dataset are women, 12.6% of songwriters are women, and 2.6% of producers are women. 9 out of 1291 producing credits went to women of color while of 173 artists in 2020, 59% were underrepresented and 41% were white.

#8M: ¿Cuál es la realidad en números de las mujeres que hacen música en México? February 2021.

This article [in Spanish] by Umu Katu presents an overview of the challenges that women face in music industries worldwide, with accompanying statistics. Within this global context, it presents data on gender representation at festivals in Latin America, and in the awarding of scholarships through the National Endowment for Culture and Arts in Mexico. Over the time period of 2012 to 2020, women make up fewer than 20% of all awardees for these scholarships.

Getting in and getting on: Class, participation and job quality in the UK’s Creative Industries. August 2020.

A report on social mobility in the UK creative industries. It finds that those from privileged backgrounds are more than twice as likely to land a job in a creative occupation, and this disparity is compounded by factors of gender, ethnicity, disability, and skill level. Unlike the FACTS survey, data was collected through a national household survey.

feat. Fem x frohfroh – Die Statistik. March 2020.

This article [in German] discusses the results of data analysis of gender representation in bookings for three Leipzig nightclubs in 2017 and 2019, compiled by Featuring Feminism [feat. Fem], a Leipzig-based platform and network for discussion and exchange around feminism in clubs, culture, and art. Their methodology for gender analysis is similar to the FACTS methodology; their categories are male, female, and unknown. In 2019, totalling up the counts for all three nightclubs, 22.6% of artists booked are female.

Counting The Music Industry: The Gender Gap. October 2019.

Consultant Vick Bain conducted a study based on the analysis of more than 100 music publishers and 200 labels, with data on the gender of writers represented by UK publishers and artists signed to labels. The findings: 14.18% of the 12,040 writers represented by UK publishers are women, while female artists make up 19.69% of the rosters of acts signed to labels. The collection and presentation of this gender data is similar to FACTS. The report also includes information on the education and talent pipeline, the industry workforce, and the barriers facing female musicians. Similar to FACTS, the report includes a Recommendations section, which we frame as a Call to Action

Orchestrated Sex: The Representation of Male and Female Musicians in World-Class Symphony Orchestras. August 2019.

This article in Frontiers in Psychology analyzes the gender distribution in forty orchestras from the UK, Europe, and the USA, which is very similar to the aims and methods of FACTS. The findings: women consistently make up less than half of players in an orchestra, and make up less than 15% of brass and percussion players. This study differs from FACTS in that it also analyzes practices adopted by orchestras for gender diversity, career patterns of orchestral musicians, and other broader topics that are currently outside the scope of FACTS.

Inégalités de genre et musique électronique en 2018. July 2019.

This is a study [in French] of bookings by gender at 11 clubs in Paris, Lyon, and Marseille for the year 2018. Like the FACTS report, their findings include statistics for women, non-binary, and mixed acts. In addition, the report includes data about the geographical origins of acts booked in these clubs – whether they were local, international, or based in other cities in France. The findings: of the DJs booked at the eleven clubs studied, 8.56% are women, 0.22% are non-binary and 0.36% are mixed groups. They found that gender minority bookings were most frequently international acts.

The list of “most festivals played in 2018”. April 2019.

This article references a study undertaken by Festicket that identified Nina Kraviz and Amelie Lens as the artists who appeared at the most festivals in 2018.

Quantifying reputation and success in art. November 2018.

This study uses network measures such as centrality to understand the role of institutional access in the successful development of an artist’s career. Their dataset includes information on exhibitions, auction sales, and primary market quotes.

Gender diversity in Wikipedia articles, ongoing.

This is a project that measures the gender diversity of the authors cited in Wikipedia articles. Its aims and methods are similar to those of FACTS in that it examines the list of citations in a Wikipedia article [its “lineup”], associates a gender with the author[s] [“artist”] of each citation, and then visualizes the gender statistics graphically.

Strengths and Limitations of the Survey

Categorizing festival line-up slots by gender is not as simple as it may seem, so we developed guidelines for counting as accurately and consistently as possible. Nonetheless, some not-so-easy-to-answer questions inevitably arise. For example: How should we count a slot that is announced under a single, easy to identify artist name who actually performed with other musicians, singers, or visual artists with different genders who are not listed in the line-up? Additionally, even if you were present at the performance, you may not have seen everybody on stage. How does one ensure accuracy in these instances? Such questions often depend upon insider accounts, leading to varying results for the same festival edition.

Another very frequent phenomenon was the presence of different information about the same festival edition in different media sources. For instance, a festival’s Resident Advisor page often lists a different number of acts than the Facebook event. In addition, programs are frequently updated as plans change, thus various versions can be found online. Quite a few websites or single web pages disappear, or substantially change over time, making it difficult to find the line-up in instances where initial gender counts were submitted a year or two ago.

On the other hand, it is a huge benefit to have many helpers who are directly involved in local music communities, and therefore can supplement online research with first-hand knowledge.

With ten years of data collection, we have a better look at trends over time, and have a significant advantage over surveys initiated more recently.

We would have liked to conduct more data verification than we did. We reviewed 54 of 159 [34%] festival editions for the current survey, but lacked the time and resources to recount more editions. Nevertheless, even if some numbers lack the verification we aimed for, the overall results should be only minorly affected. In addition, we assume that any potential errors in counting festival acts are random rather than systematic. Thus, errors should not systematically bias the results in any one direction, but instead even each other out.

Assessing the categories of attendance, curators, and public funding is extremely difficult without the help of the festival organizers. The publicly available information about these categories is very limited. Most festivals do not disclose the names of their artistic direction team. This again illustrates the importance of communication with festival organizers. We believe that by involving curators and organizers, we can raise awareness and foster reflection about festival curation. In general, we often face a lack of transparency that limits gathering and analyzing data, as well as our ability to catalyze positive action to make the electronic music industry more representative.

Selection bias is probably one of the most significant causes for possible distortion of the results. For example, organizers of festivals with a higher number of female acts might be more willing to take part in the survey, leading to an overestimation of female acts overall. Remedying this bias by counting all electronic music festivals in existence is unfortunately not achievable. In addition, publicly available data for some countries or regions are sparse and thus not representative.

We counted the number of acts for each festival, not the number of persons on stage. Assuming no systematic gender difference in the number of persons in female, non-binary, and male acts, the analysis would yield similar gender proportions if acts or persons are counted. Whether this assumption holds for electronic music is unclear. Collecting data about the number of persons and not the number of acts [as we did] might lead to different results.

One reason that we are interested in ascertaining whether a festival received public funding is to see if there is any relationship between public funding and the number of female and non-binary artists on the line-up. For example, the Musicboard Berlin conditions festival funding on the following: “…ensure the participation of at least 50 percent female, non-binary, and queer artists.” We do not assume all institutional public funding has such requirements, but there are indications in our data that publicly funded festivals have higher proportions of female acts.

5. ADDITIONAL ISSUES OF DIVERSITY

Counting Race in FACTS

Electronic music festival line-ups, at least in Europe and North America, are overwhelmingly dominated by white artists. This is particularly troubling, as electronic dance music has its origins in queer, Black, and Latinx culture. Without these innovative DJs, artists, and audiences of colour we would not even have the subject of our study today. The Trouble Makers have discussed quantifying race in electronic music festival lineups for several years, and it was in 2020 that we began to take action to understand how to approach the issue in a way that would provide meaningful data. We questioned if it is possible to categorize and quantify race within the framework of this survey. While it is relatively straightforward to categorize an artist’s gender from biographical material [and, indeed, more and more artists are listing their pronouns on social media and their websites], the specific categories we could use for race are far more complex to determine. Census data, for example in the United Kingdom, presents an apt example of the challenge, as the list of ethnic groups is different depending on if the location is England/Wales, or Scotland/Northern Ireland. In addition, racial discrimination may vary from country to country. An artist considered white in one country might be considered a person of color in another country, making it difficult to summarize findings across countries.

The social construction of race, the ongoing structural discrimination based on racism and racialization, and the ways in which white supremacy has wielded the idea of race to commit severe harm in the world are important considerations. We conducted several interviews and found that race is a difficult issue for anyone who is thoughtful about the topic. People are in the course of deconstructing and challenging traditional racial categories. We need to appreciate that we are in a period of flux, and that this is a subject worth wrestling with. The best way to respond to the challenge is to allow people to use the categories of their society, to let people define themselves [e.g., via an artist survey]. Given the nature of this grassroots, voluntary FACTS project, executed by a very small number of artists in their spare time, it quickly became clear that our options to acquire reliable data about racial self-identification are extremely limited without the aid of, for example, an academic institutional partnership. Our attempts to find potential partners for this purpose were not yet successful. Consequently, we decided the best way to begin was with a qualitative [rather than a quantitative] study, which has taken shape as a series of conversations

We started to consult with artists of color from the female:pressure network about their thoughts on how the FACTS survey could approach race, asking them these three questions:

[1] What are your thoughts about the electronic music scene and the visibility of artists of color and marginalised ethnic groups?

[2] Would you like to give us insight into your personal experience in the scene?

[3] Do you have any ideas about how to analyse the representation of race and ethnicity at festivals of electronic music in the FACTS survey?

From these conversations arose several important points to take into account, one of them being that every world region has its own definition of race and of racial categories.

More specific issues include:

- Dependence on the goodwill of a relatively small number of gatekeepers in order to get booked and recognized in a scene where artists of color and marginalized genders are mostly underrepresented.

- Curators, booking agents, and other decision makers who act effectively as the gatekeepers of festival lineups seem to be predominantly white and male. Moreover, key festivals are monopolised by prominent booking agencies.

- The status of record labels and releases of music are factors that affect the perception of and the demand for artists in the booking ecosystem. Women, and gender minorities are underrepresented as producers and as signed artists, which limits their visibility.

- Not only is the lack of representation of artists of color problematic, but also a kind of tokenization that overlooks the local artist who belongs to a marginalized group in favor of an international artist.

- The fundamental role of class [and caste in India] and hence economic and cultural capital.

- The undervaluing and lack of acknowledgement of the work and contributions of women, artists of color and gender minorities to the music industry and the preservation of white and/or male dominance as a source of culture and innovation.

- Discrimination against women and gender minorities intersecting with racism and lack of economic and institutional power.

- A perceived huge gap between genders and races in regard to artistic opportunities and potential to earn income. Where women, artists of color and gender minorities are included, opportunities are typically limited to artists who meet Western standards of beauty and desirability, cultural norms and in some cases, particular ethnic groups [in Europe].

- Limited access to means of production, knowledge resources, mutual exchange with peers, and lack of kindred role models.

- The necessity of education and awareness to achieve equity.

- Another issue of diversity and inclusion/exclusion that is increasingly brought into focus is that of artists and also attendees of festivals with disabilities.

- Interviewees also challenged the white and Western framing of discussions about diversity and inclusion. Who is doing the including? They called for more space where marginalized groups can voice what is important to them.

- The significance of confidence-building measures in case we implement the artist survey [i.e. asking artists to self-identify]. Who researches might be quite as important as what is being researched. We must not come across as a “bunch of white saviors”.

- While most interviewees think that numbers are useful tools to raise awareness about structural lacks of diversity, there are different opinions about how such data could be obtained. A minority of our interviewees suggested we should just go ahead and count according to the outward appearance of an artist and establish just a few very rough categories. The majority is more careful when it comes to the technical approach to such data collection and would prefer to be asked about how they identify before being put in a box by a stranger.

- General tokenization of a few artists of color who then might even be confused with one another if they happen to have a similar complexion.

- The need to establish independent structures and networks for mutual support.

- Artists of color, women and gender minorities face a wide range of physical, mental and emotional challenges when they have to teach people, advocate on their own behalf and rehash their bad experiences continually.

- Hope for future generations and perceived positive change of discourse, growing empowerment.

We plan to continue our work on this project, for now independently of FACTS, as we work to discover the best way to collect and analyze data about artists of color in electronic music festival lineups.

Female and Non-binary Artists and Slot Hierarchy

As for other future lines of inquiry, it would be interesting to know if female and non-binary artists are generally booked in less prominent time slots. It would be difficult to quantify this data, but perhaps a count of the gender of headliners would shed some light on this topic.

Female and Non-binary Artists in Leadership Roles

As Lazer Guided Reporter mentions in her MA dissertation, “There is a limiting of space in the industry where women can be visible in positions of musical control.” It would be helpful to have collected more data about festival organizers than we did, but this information was impossible to find for many of the festivals that we included.

Ageism

As made clear by the 2021 Resident Advisor article, “A Barrier to Being Seen: Ageism and Sexism Intersect on the Dance Floor”, there are additional barriers for women DJs who are older. It would be enlightening to collect data on the age of the performers in lineups, though certainly time consuming and not possible in many cases as many artists do not list their age in their online presence. Again, perhaps a count of the age ranges of headliners would be useful.

Ableism

The discrimination in favour of able-bodied artists and audiences has gained increasing attention. Institutions like the Musicboard Berlin, for example, started to focus their funding programs on projects that foster the participation of people with disabilities. The nonprofit organization Half Access maintains a database that provides accessibility information about venues to help disabled people to prepare for their visit, an issue highlighted by recent articles such as “Concert Venues Assume Disabled People Are No Longer Music Fans” in the Disabled Spectator and “Live Music Should Be More Accessible for Disabled Fans” in Vice, which describe the barriers faced by disabled fans who wish to attend a concert. It would be illuminating to collect data on which festivals have clear, easy-to-find information on the accessibility of their event, both for performing artists and audience members.

6. CALL TO ACTION

Despite the rise in gender diversity at electronic music festivals over the past decade, the proportion of female and non-binary acts is still significantly lower than that of male acts. We would thus like to share some suggestions from our own experience and that of many friends and colleagues to help improve the gender diversity among music festivals.

In preparation for this report, we analyzed several festivals which have been included in every edition of the FACTS survey and which showed a trend toward greater gender diversity. We emailed the organizers of these festivals to ask them how they achieved this trend, whether any conscious action was taken, and what they learned in the process. Several organizers wrote back to us, and some of their feedback has been incorporated into the list below.

Here are some elucidating comments from the organizers we contacted:

“On a personal level it was impossible to not react towards gender diversity improvement movements and campaigns everywhere (in the past few years)…the action taken was quite simple actually…it was all about researching more female artists and booking them…I think that the most important lesson I’ve learned is the power that a more diverse line-up has on a local grassroots ecosystem…the snowball effect it causes makes me the happiest person…you slowly start to perceive that music has the power of social and political change.”

Chico Dub of Novas Frequências

“The catalyst for the increase was/is the ongoing realization that unbalanced line-ups don’t occur because there are no FLINTA artists to book but because they don’t get booked as often and paid less, which results in a lack of representation and general visibility in the art and music scene…As a festival, we have to realize that we are part of and acting in a system and we have to break out of that actively…I listen to FLINTA artists, buy their music, go to their parties and shows. As soon as this becomes a normal part of your music consumption practices, there is really nothing you have to change except booking artists who fit the best for your festival and shows. If the consumption of music changes, the booking changes as well…the underrepresentation, not only of FLINTA artists but also of BIPOC and LGBTQ+ artists is still going on and something you actively have to break through in your music consumption and booking practices. Here, the music industry as a whole, and that includes media coverage, needs to commit to active changes. In conclusion we’ve learned as a festival that the effort for a balanced line-up not only broadens your knowledge and taste in music as bookers but also really makes a festival line-up much more interesting, diverse and elevated.”

Nora Wenzler of donaufestival

“Gender equality is important, but also other forms of diverse representation – in terms of race, sexuality but also geographic representation. There is a noticeable general rise of consciousness when it comes to the need of diversity the music industry (and everywhere else, in fact) which has undoubtedly been also an effect of years of work of collectives like female:pressure, among others, which has given courage to a lot of women and female-identifying people to make music and become more visible. That’s great and makes also our work easier having so many amazing female creators to choose from when programming. It is also important to include female-identifying programmers and curators in the process. We actively look for and try to encourage female-identifying artists to perform or foster collaborations which I think is important and encouraging, especially to people at the beginning of their careers. Also organizing workshops within our Unsound Lab program (workshops for young music industry professionals) about intersectional diversity in the music industry.”

Gosia Płysa of Unsound Krakow

In addition to presenting gender data, we also wish to promote improvements for the future and suggest actions for festival organizers, artists, journalists, policy advocacy groups and politicians, and festival attendees. These lists comprise actions suggested by the Trouble Makers as well as members of the larger female:pressure community.

Points of Action for Festival Organizers

- Members of majority groups should actively show solidarity with minorities in the field; see, for example, the GRAMMY Awards Show Inclusion Rider.

- Festivals, in particular larger festivals, should consider a diversity, equity, and inclusion committee.

- Believe in a multi-faceted and heterogeneous electronic music scene. Strive for a less capitalistic approach to your listeners by supporting a more performance-oriented music culture.

- Book more people of different genders. Book more people of colour. If you believe they are unfamiliar to your audience and/or won’t bring in enough money, use your resources to invest in good press work and consider installing local/underground stages and promote a general ethos of inclusivity at your events. Network and collaborate with booking agencies that have diverse rosters and inform yourself about and/or connect with festivals around the world that have diverse line-ups.

- Delegate your curating power. Inform yourself about maker spaces and workshops that serve underrepresented groups in music production and skills. These types of community spaces have important knowledge to share. See, for example, Hyperreality Festival’s invitation of crews, clubs, and collectives to curate different time slots.

- On the organizational level, install a mixed-gender team to program your festival’s line-up.

- If you are interested in having a diverse line-up that reflects the state of the art in electronic music, you might take actions such as making public calls for participation and specifically make diverse representation a criterion for selection. Be intentional and transparent about your inclusivity goals.

- Support your local underground scene by connecting with record dealers and music journalists who are experts in the field.

- If you have the capacity, include discussion and skill-sharing programs to promote diversity and inclusion in the electronic music industry. Host workshops on topics such as music production, gear selection, music promotion, and other music business skills. By facilitating skill-sharing workshops, you can foster a community where budding artists can connect with one another and the scene. You may even cultivate the skills of artists who may play at your festival in the future. We believe that the relationship between artists and festival promoters will change for the better as a result. Workshops and discussions can be funded in a variety of ways, from ticket sales to donations to institutional funding from socio-cultural programs, for example.

- Ensure safe working conditions and accountability at your festival by training personnel in cultural sensitivity and inclusion, so that all artists are treated with respect, regardless of race or gender. Consider often-overlooked details such as cooperative and safe childcare for the families of artists and staff and gender-neutral toilet facilities.

- Initiatives like the Awareness Akademie in cooperation with stakeholders could develop guidelines to create a certificate for clubs and festivals. If a festival complies with such guidelines, they would be able to promote their events with the logo and certification.

Ensure safe working conditions and accountability at your festival by training personnel in cultural sensitivity and inclusion, so that all artists are treated with respect, regardless of race or gender. Consider often-overlooked details such as cooperative and safe childcare for the families of artists and staff and gender-neutral toilet facilities. - We would like to see widespread adoption of a “Code of Conduct,” a guideline for best practices for festivals to accommodate the societal and cultural implications that their programs, advertising, and publications produce, by electronic music festivals. We believe it is never and has never been “just about the music.” Festivals have interests such as: obtaining fame or relevance, having economic success, or promoting particular agendas—many times of personal importance—such as the advancement of a genre or political worldview, among others. A good example of such a code was posted in 2018 by We Have a Voice. Another good example is the Code adopted by the Ableton Loop Summits. Tarmac Festival includes this line on their website: “racism, sexism, antisemitism and all other forms of discrimination won’t be tolerated and will lead to immediate banishment.”

Points of Action for Artists

- Connect yourself with local and/or global networks and seek out resources for female and non-binary artists, many of which are listed on the female:pressure website.

- To artists in positions of relative cultural power, in particular white cis-men, we applaud those of you who have shown solidarity with female and non-binary colleagues by boycotting festivals when their line-ups fail to be diverse or inclusive. We think strategies such as this are effective at making promoters and curators question their policies.

- Learn what it means to be an ally. Make the effort to understand and overcome your biases. Consider how you can use your position to empower gender minorities and marginalized artists in the scene, listen, and take action consistently.

- Inclusion riders can be powerful tools. See, for example, DJ/Producer Om Unit’s inclusion rider. Breaka and object blue also use inclusion riders. More on inclusion riders can be read at the Electric Hawk.

- If you are offered a gig but cannot accept it, consider recommending to the hiring person an artist from an underrepresented community that you know [or know of]. Please, though, be sure only to do so for gigs where you feel this person will be relatively safe, both physically and psychologically.

Points of Action for Journalists

- Make sure that the pieces you pitch reflect the diversity of the scene.

- Cover equality initiatives within the scene, such as when an artist adopts an inclusion rider.

- Cover collectives, communities, and events that continue to do excellent work in regards to gender and racial diversity; to show that it’s possible, more so when these initiatives are successful.

- Include commentary from artists of marginalized genders, especially those of color, on a range of topics, not just equality and race.

- Provide a broader perspective on women DJs, such as their technical acuity, whether they work in other areas such as production or promoting events.

- Incorporate women into other commemorative initiatives outside of Women’s History Month.

- Ask the crucial questions about booking agencies and funding opportunities within the scene: In what ways are booking agencies diverse with respect to their staff, ownership, and rosters? Who is receiving funding?

- Do your own internal work. Biases regarding race, gender, age, ability, and so on, will show up in the way you ask questions and how you communicate stories.

- Ask questions of artists and relevant industry people about gender and racial diversity in interviews. Put them on the spot! Normalize talking more freely and frequently about these issues.

- If you know that an artist subscribes to sexist or racist views, reconsider writing about them or promoting their work.

- Think more critically about who and what you are writing about and whether this person/topic is having a positive influence on the scene.

- Aim to promote artists of marginalized gender and non-white artists as often as possible.

Points of Action for Policy Advocacy Groups and Politicians

- Determine whether or not your local public funding organizations attach diversity requirements to disbursement.

- Create and support initiatives for public arts funding. Many under-represented groups do not have the personal wealth to grow their careers; creating funding opportunities [especially ones that highlight diversity] will often result in the support of artists who may otherwise be prohibited from reaching full potential because of financial barriers.Determine whether or not your local public funding organizations attach diversity requirements to disbursement.

- Understand that arts initiatives serve as a useful knowledge base for evaluating how structural discrimination affects individuals and are a crucial component of freedom of expression [see, for example, The Council of Europe’s Manifesto on the Freedom of Expression of Arts and Culture in the Digital Era].

Points of Action for Festival Attendees

- If you see that a festival is creating an unsafe space for artists and/or attendees, please contact the festival organizers. It is possible that they are unaware of the incident[s]. If they are unresponsive, or invalidate your concerns with their response, consider raising awareness on social media [if you feel that you will not be attacked for doing so]. Abusive organizations often depend on the silence of onlookers to continue their bad practices.

- If you feel safe to do so, contact and/or call out festivals on social media when you see a lineup comprised entirely or mostly of white cis-male artists. Festival organizers are very motivated by what they perceive will bring the largest audience to their carefully planned event. Change their perceptions of what audiences want by demanding more diverse lineups.

7. CREDITS AND PROVISIONS

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr. C. Patrick Burrowes, historian and humanities scholar, for his counsel and guidance in the initial stage of our research regarding the representation of Black artists and artists of color in electronic music culture.

We wish to thank the artists we interviewed for sharing their experiences and thoughts about race and ethnicity in the electronic music scene.

Disclaimer

We performed this survey to the best of our knowledge, trying to validate and cross-check as much data as possible, often using content from festival websites showing line-ups and programs. We welcome any feedback in case of accidentally erroneous data.

Data Sharing

Data sharing is an important way to increase accountability and transparency of a research project. We consider data sharing valuable to validate our findings and to open the opportunity for data to be combined to allow for further analyses and comparisons. Thus, we are happy to share the final dataset from the FACTS Survey 2022 upon reasonable request. Please email data@femalepressure.net for more information.

Credits

Core Survey Team

Angelika Lepper [Utting am Ammersee]

Corina MacDonald [Montreal]

Jaquelyne Kwenda [Johannesburg]

Meg Wilhoite [East Bay]

Michelle Endo [San Francisco]

Stephanie Roll [Berlin]

Susanne Kirchmayr [Vienna]

Tanja Ehmann [Berlin]

Graphic Design

Elisa Metz [Cologne]

Photography

Frederike Wetzels [Cologne]

Press

Noémie Burel [Berlin]

Data Collection Helpers

Alejandra Cardenas [Berlin]

Anja Weber [Berlin]

Caro Churchill [Manchester]

Christina Nemec [Vienna]

Jules Marks [Brighton]

Kim Pohas [Los Angeles]

Maxi Allesch [Vienna]

Maria Hamilton [Madrid]

Olivia Louvel [London]

Paulina Lasa [Mexico City]

Paulinhx Desbats [Berlin]

Yvonne Kiely [Galway]

plus the many individuals who sent data using our online form. Thank you!

8. APPENDICES

For the Appendices please see the PDF, pages 52-104

Appendix 1: Gender Proportions for All Festivals by Year [2012 to 2021] p.52

Appendix 2: Gender Proportions by Country and Year [2012 to 2021] p.75

Appendix 3: Gender Proportions by Country, Festival, and Year [2012 to 2021] p.81

Appendix 4: Gender Proportions by Festival Line-Up Size [2012 to 2021, 2020 to 2021] p.98

Appendix 5: Ranking of Festivals by Female Proportion [2020 and 2021] p.99

Appendix 6: Ranking of Festivals by Male Proportion [2020 and 2021] p.102